You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Regulators’ category.

Following the publication of a document on Islamic Finance (IF) by Austrade this week, perhaps we may get something serious in the way of development of this area in Australia.

Interestingly, the Trade Minister, in releasing the document, announced the release of a new product by Westpac – I wonder when Westpac will get around to announcing it. I would not find anything on their website. My guess is that this is just a toe in the water, because if they expected it to be a significant part of their business, they would have to make an ASX release about it. In that, I think they are right. A single specialised product is not going to be big in the context of and institution that size. That said, getting some credibility and experience will be a good thing.

For those interested in the area, a full read of the Austrade publication would be a useful thing. It provides a decent discussion of the IF market (although some of the data seems a little out of date as market growth has been hit by the Dubai problems). The issues identified in it are similar to the ones I identified a while back – the tax and regulatory structures in Australia need to be changed to remove the artificial impediments, find or develop appropriately qualifies Islamic scholars and we need to increase the knowledge base of banking professionals in Australia.

None of this is impossible – the regulatory stuff can be done quickly by essentially copying (at the State level) what Victoria has done and, at the Federal level, copying what the UK has done in regulation terms. Improvements on these could be made, but this would be a good first step.

Good to see at least something happening, though. It is a fascinating area of banking. In the mean time, read the Austrade document. It is pretty good.

It looks like the IASB is really interested in our opinion on the own credit risk issue. If you want to give them your opinion (and mine is pretty clear) then you need to become a registered user of the IASB website (come on – you know you are really interested and you do not have to admit it to anyone) and then email them at “owncreditsurvey@iasb.org”.

It would be worth doing if it gets them to a sensible position. Of course, many banks and other enterprises may find it “sensible” to allow the inclusion of own credit risk in the value of a liability – it would serve to reduce the disclosed value of the liabilities of the company, perhaps taking a failing enterprise to a position where they are then able to show a positive net worth. It would also improve the capital position of banks.

That would be a truly perverse outcome.

There is a heck of a lot in this, so I have split this into two posts – one on the exposure draft (ED) on amortised cost (AC) and impairment and one on the (now released) “final” standard on classification and measurement – which is also long and will take a day or so. If you want to know why that is in scare quotes, go there when it appears.

As you can tell from the title, this is the one on amortised cost and impairment.

To read what the IASB has to say on this, go here for the press release and here for the content. As previously advised, I would suggest sticking to the basis for conclusions (BCs) as they are more readable, but if you want to submit a comment, you will need the exposure draft.

Having now read this a couple of times and listened to the webcast, I am still uncertain in a number of areas. I think this is going to take some work over the next couple of weeks to get sorted out and then the (now) three years’ implementation period to get roughly right.

That’s right – three years. As part of the release of this section the Board said that the earliest date for mandatory adoption will be 1 January 2013 – with early adoption permitted. This is apparently as they realise the complexity of this (I feel like saying no and a certain four letter word at this point) and to align with the prospective new insurance contracts standard. It may even be delayed past 2013 if that standard is delayed. In the webcast to night they were at pains to say they did not want to have insurance companies unduly inconvenienced by having a double change of standards.

I will work through the ED in the order in the BCs as I have advised reading those. Where there is something in the ED that I find interesting I will cover it even if it is not mentioned in the BCs. Read the rest of this entry »

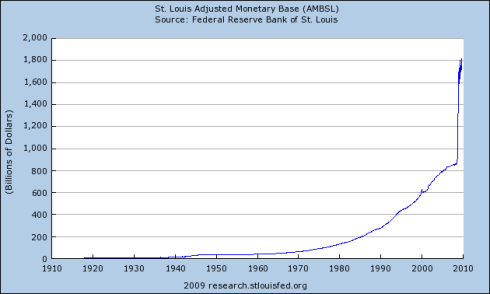

Following on from this post nearly a year ago I thought an update may be of interest.

Clearly, the situation has not improved greatly since then and the reservations I expressed about this last year are still relevant today – but if this story proves correct it may be that the situation is to be resolved at least in the short run. At least it has not got notably worse.The thing with the reverse repos, though, is that the money will eventually re-emerge into the systems as the deal(s) unwind, so this is only a temporary cut. Additionally, the paper that the fed would be issuing (if this is correct) will also normally be negotiable, so this is not as real a cut as it looks.

I am not sure if they intend to keep it that way (i.e. eventually allow all of that cash from the unwound repos to go back to the banks) or if they will be looking to unwind the position completely and return the monetary base to trend – i.e. about USD900bn, representing a long term withdrawal of about half of the current amount.

Either way, it looks like the gigantic experiment is set to continue for a little while yet – just with a little pause.

As for Australia – we could, by comparison at least, be said to be models of conservatism in monetary policy.

A fairly late night for me – just finished this webcast (sorry, slides only ATM – they are releasing the webcast later). While the IASB were pitching this as a bit of a status update, they could not help but give some interesting pointers on where they are going and, as a result, what issues they feel fairly strongly about.

The main issues identified in the recent ED were:

- There seems to be a fair amount more clarity needed about the

instruments that were to be allowed to be treated as amortised cost –

the wording about “basic loan features” was considered a bit woolly.

I would agree – but to me this should be able to be handled in some application guidance not in the main standard. - There remain a number of questions around the own credit rating

issue – if you fair value your own traded bonds you are implicitly

including your own credit rating. This issue seems to be rather thorny.

It may not go any further in any case as the IASB seem to be backing

away from this, calling the method “not decision useful”.

I would disagree – the issue is not difficult. An entity should not be able to recognise any possibility that it will not be able to meet its obligations as and when they fall due in any way, shape or form. This is a violation of the going concern principle.

Other issues covered were:

- Progress on the impairment model seems to be progressing – the use

of an expected loss model seems to be one of the barrows the IASB are

pushing, with the difficulties seen to be more around cost and

practicality than general principles.

They are proceeding to establish an experts advisory group to advise them on operational issues, application guidance needed and to facilitate field testing.

I may have misunderstood here, but I do have a problem with this and on several levels. For anyone other than a very large corporate or a sizable bank this is not cheap to do. In Australia at least, this standard applies to all entities, so this is likely to be a significant cost.

The other main problem I have is one of the whole principle. An EL model is inherently forward looking – yet a “Statement of Financial Position” is a point in time concept and an income statement is (by definition) backward looking. To me, the current impairment method is one of the strengths of IAS 39. Making it easier would be good. Violating the whole principle of financial statements is not. This seems to be one of the areas that the BIS would like to see in – but I have given my opinion on that before. I will be keeping a close watch here. - Our old favourite of hedge accounting got a good look in as well,

with an ED likely to come out in December. The changes here may well be

extensive, with the IASB looking to simplify cash flow hedge accounting

and making the fair value method more like the cash flow hedging. This

could be achieved by changing it to have the hedged item left at

amortised cost and changes in FV of the hedging instrument going through

OCI.

One word here – “yay”. If you want some more words – I have dealt with many clients that just gave up on this whole area – sometimes on my advice – as it was just too difficult. Changes here (the FAS 133 shortcut method, please and at first impressions I like the possible new FV method) would be very good.

The other areas that were discussed were the likely effects on the upcoming insurance standard(s), particularly WRT to 2 above; the possible removal of the cost exemption for instruments that are difficult or impractical to value and some consideration of what to do with these in interim accounts.

The IASB will be moving to weekly board meetings to try to get all this done in the timescales they have set themselves. Personally, I think this may be a sign that they are preparing to slip the deadlines.

The questions period was short – and the IASB wanted only process questions – but they could not really help themselves on a couple. The best question though, was on the convergence between IAS 39 and FAS 133, in that they both have very different timelines for releases but both are saying they want to converge. All I can say is “get on with it guys”. One standard (as long as it is simple and makes sense) is much, much better than two (or more).

Just for those particularly interested in where IAS 39 is going (OK – you do not need to admit it by putting your hands up). The IASB will be holding a webcast on how they are going:

On 23 September 2009 the staff of the IASB will present two identical webcasts on the project to replace IAS 39. The webcasts will be held at 11am and 5pm GMT. The webcasts will address the following:

•an overview of the feedback received on the Exposure Draft Financial Instruments: Classification and Measurement, the Request for Information – impairment of financial assets and the Discussion Paper Credit Risk in Liability Measurement ; and

•the next steps in the project to replace IAS 39 taking into account the discussions at the September Board meeting

Both presentations will be followed by a Q&A session where registered participants can submit questions via the online facilities.

If you are interested, try attending. It is unlikely to be too exciting*, but it may well be worthwhile.

* …by design – one thing you do not want is too much excitement when discussing accounting standards.

Thanks to financialart for the point at the BCBS’s response to the partial draft of the replacement to IAS 39.

Frankly, though – I am disappointed by their (the BCBS’s) response – which I shall refer to as “the document” from this point on. Overall it is a long wish-list which is in places self-contradictory and makes a couple of evident misunderstandings on the role of IAS 39. For a start, the document makes it look like IAS 39 is just for banks, when it applies to all IFRS reporting entities – and so it has to be able to work for everyone, not just banks.

Perhaps using the old “Good, Bad and Ugly” criteria would be useful – but in reverse order.

The Ugly (the Contradictory or Confusing Parts)

To make one thing clear up front – IAS 39 is an accounting standard, not a prudential standard. Its role is to provide accounting information to external users. Accounting, by its very nature, is (and should be) concerned with facts and (where possible) should avoid as far as possible the use of models to provide accounting information. At times this is not possible (for example in attempting to determine how much of a loan portfolio meets an IBNR classification) but where models must be used they should be very restricted in scope and the accompanying disclosures should be clear. Prudential standards, however, need to be forward looking to a much greater extent as they are designed to answer very different questions.

Accountants are meant to answer questions like “How much was that position worth on balance date?” and “What was the net profit for the year?”. Prudential rules need to be able to answer questions like “What is the probability of this bank failing over the next 12 months?” and “How much liquidity is enough?”. These are very different questions – but the BCBS seems to be trying to have an accounting standard that does both.

The document is also asking (and I agree with it) for a simpler set of standards – they devote a whole section to this request – and then in subsequent sections they ask for what could only be provided through increased complexity. For example, a move from an incurred loss model to a more prudential style one would effectively mandate that every single publisher of financial information using IFRS (i.e. every company in Australia) would need a prudential loss model for their creditors. The new standard would also have to spell out how that was to be done and this would represent an enormous increase in complexity, particularly for smaller banks and non-banks. If this is not to apply to everyone then we would need at least two (differing) impairment models, increasing complexity even further.

The document is also calling for the new Standard to be introduced with a timetable consistent with “financial stability”. This is nonsense. A new standard takes years to write and consult about – this one up until 2012 – so trying to time its introduction is just silly. If it is a better standard it will improve reporting, and so will enhance stability. If it is not, it will hurt and so should not be introduced. Either way, trying to time the end of a multi-year process to enhance “financial stability” is just silly.

I would also add the last sentence of an otherwise Good first section into here – the main point of accounting standards is to provide (as far as possible) “truth and fairness”. Increasing “market confidence” should only come from being respected, not from attempts to tweak the standards to hide the truth.

The Bad

The “tweaks” referred to above are in para 10 of the document, where there is a call to “de-link” the valuation from “certain aspects of income and profit recognition”. The call here is not clear at all and could result (if incorporated in the Standard) a significant role for management judgement in the valuation of difficult to value items. This element will always have to be there, but the sorts of language incorporated here is just dangerous.

Probably the worst misunderstandings in the document are in the area of fair value – with the writer of this letter mixing up the two related (but not identical) concepts of fair and market value. IAS 39 is pretty clear that there are differing ways to measure fair value and only the first (market value in an orderly, liquid market) is really discussed here. The author clearly confuses the two – witness point 4(b) in the document, where the author says that “the new standard should…recognise that fair value is not effective when markets become dislocated or are illiquid”. Ahem – the current standard does that, as does the new draft.

Another Bad bit is directly above – an accounting standard should not “…reflect the need for earlier recognition of loan losses…” than the current standard does – that is a prudential standards’ role. Doing it here would just go back to the old system where management were (to an extent) allowed to put whatever they liked into the provision for doubtful debts. The current method, while at times complex, at least is less susceptible to manipulation.

The Good

To be fair, though, I should recognise the excellent parts of the document. The first section is a combination of motherhood and useful statements (except for the last sentence). The call for more meaningful disclosures is good, and one I have made before. IFRS 7 is both overly complex and too simplistic simultaneously – a good trick at the best of times. The call in the letter to have it revised is timely – the suggestion to make the disclosures in a more standardised format is a good one.

Section 2 and 3 are good – but are contradicted (as covered before) by (inter alia) paras 12 onwards. The rest is broadly good – but mostly just covers areas that are self-evident anyway.

Overall, if this were given to me by a new graduate attempting to write a wishlist for the new IAS 39 I would hand it back with a few complimentary notes on it applauding their efforts. Coming from a major regulator (never mind the peak banking body) I can only shake my head.

I have just started reading a book by Tim Carney entitled “The Big Ripoff” and he makes many of the points I have made time and again – the effects of regulation are generally not the ones you would expect.

The fans of regulation are generally taken to be opponents of “Big Business” and they call for more regulation as a counter to the (alleged) pernicious effects of having large companies. Most of these effects are easy to see – strong pricing power, reduced service and many other things that are bad for the consumer.

The argument that Carney puts forward, though, is one I have been making for some time – both on this blog and elsewhere. The argument is a simple one. The more regulation you have in a market the more that regulation will favour the big suppliers – i.e. the larger incumbents – over the smaller incumbents, any potential new players, and, crucially, the individual consumers. So the more that you regulate the worse the situation gets for everyone but “Big Businesses”.

The reasoning is simple to see if you think about it – compliance is expensive. I know this as a simple fact – and my fee base confirms it. It costs money to comply with regulation. The more complex it is the more expensive it gets. For example – complying with the (old) Basel I Accord was a simple exercise. While it took a fair amount of work to get compliance when it first came in in 1988 / 89 most banking systems could comply with it fairly quickly and, importantly, cheaply.

While Basel II is a much better (i.e. risk sensitive) set of standards there is (I think) no-one out there that would claim they are simpler than Basel I. The amount of money that even a small bank following the Standardised / Basic methods of compliance had to spend was a fair leap from the amount they had to spend to spend under Basel I, and the amounts you have to spend to comply with the Advanced methodology (and therefore to get a substantial capital advantage) was many, many times more.

There is simply no way that a small bank or a new player can afford this without the belief that they will become a big bank (and therefore Big Business) as a result.

Even to keep the people needed to continue and upgrade these systems is expensive and needs a high (and profitable) turnover. There is no other way.

All of this means one thing – that more regulation makes it relatively more expensive for small businesses to operate that for large businesses and it imposes high barriers for new entrants into a market. Regulation therefore tends to help big business, not hinder it.

BTW – I should add that a post at catallaxy reminded me to write this one.

I have been away from the purely banking risk area for a little while, so I had dropped my regular visits to the BIS website. Having headed over there for some stats recently I noticed how much they had beefed up their coverage.

A few interesting things have also appeared.

Deposit Insurance

The CP on deposit insurance that they issued in March has been updated into a full set of recommendations – the paper is here. Regular readers would know my opinion on deposit insurance, but in general the principles in this paper are sound. A worthwhile note is on page one:

The introduction or the reform of a deposit insurance system can be more successful when a country’s banking system is healthy and its institutional environment is sound. In order to be credible, and to avoid distortions that may result in moral hazard, a deposit insurance system needs to be part of a well-constructed financial system safety net, properly designed and well implemented. A financial safety net usually includes prudential regulation and supervision, a lender of last resort and deposit insurance. The distribution of powers and responsibilities between the financial safety-net participants is a matter of public policy choice and individual country circumstances.

Advice to our PM and Treasurer – do not do this in a hurry and in a poorly thought out manner. Nuff said.

Basel II Changes

Pillar I

The latest tweaks to the main Basel framework seem to be trying to do a little stable-door shutting on securitisation – with a fair bit of language added around understanding the risks and a few risk weights being increased.

Pillar II

The language of the amendments to Pillar II is also interesting – this places a large amount of emphasis on improved risk management at the banks, including reporting structures, concentration management and, in particular, the off-balance sheet stuff.

One recommendation in particular is interesting – the separation of the CRO’s office out of the business lines to report directly to the CEO and Board (pillar II amendments – 19).

Securitisation

This one is also good (pillar II, para 40):

A bank should conduct analyses of the underlying risks when investing in the structured products and must not solely rely on the external credit ratings assigned to securitisation exposures by the CRAs [credit ratings agencies]. A bank should be aware that external ratings are a useful starting point for credit analysis, but are no substitute for full and proper understanding of the underlying risk, especially where ratings for certain asset classes have a short history or have been shown to be volatile. Moreover, a bank also should conduct credit analysis of the securitisation exposure at acquisition and on an ongoing basis. It should also have in place the necessary quantitative tools, valuation models and stress tests of sufficient sophistication to reliably assess all relevant risks.

I would agree – but it should not take a regulator to tell a bank

this. I wonder who is going to pay for all the extra analysts – or will

banks just walk away from this market?

The whole document is worth a close read and I should get around to it

soon. From my scan, though, I cannot see it having a significant impact

in Australia. APRA was already doing most of this – but the changes to

securitisation may cause some heartache amongst those institutions that

rely on them, such as many credit unions and other smaller ADIs. I would

be looking to the specialist mortgage providers and the bigger banks to

benefit from these.

Liquidity

As expected, as well, the BCBS has boosted its look at liquidity – with almost as many mentions in the 41 pages of this as in the 400 of the Accord itself. Given much of the problems (like those at Northern Rock) at least started as liquidity issues this is not surprising. The language looks mostly drawn from the relevant Sound Practices document, but this incorporates it into the Accord itself. Again – not much to see here, as much of this is already in the relevant Australian liquidity regulation, and APRA is well across this.

Stress Testing

Brand new is a whole two pages on stress testing. As I highlighted nearly three years ago in one of the perennial favourite blog posts here – the original accord had little to say on the subject beyond telling you that it had to be done. The two pages here go some of the way to addressing that gap, but not nearly all the way. They are obviously leaving the wording fairly general here and leaving it up to national regulators still.

Pillar III

Much of this is focussed (as can be expected) on improving disclosure around the areas that have caused problems recently. Almost all of the changes to Pillar III are about increasing disclosure of securitisation exposures – with some consequential changes to the CRM stuff. None of this should cause any banks to sweat too much – these sorts of numbers have been demanded of the banks by the regulators for a while. It is just publishing the disclosures rather than sending them to the regulators.

Wrap Up

All of these comments, though, are fairly preliminary. I will need to go through this in a bit more detail and give it some thought. If I have missed anything, feel free to point it out in comments.

It’s good to know that I am not the only one looking at this proposal and not knowing whether to laugh or cry. The post titled “A Mighty Wind” over at The Dealmaker’s blog is well worth a read. Just watch it though – the language is not entirely worksafe.

There are some great quotes in there:

Forget the no doubt significant fact that substantial portions of the Administration’s regulatory proposals were authored by products of a government-to-industry-to-government merry go round like Hank Paulson, Larry Summers, and Tim Geithner. Forget the fact that the Administration is said to have consulted heavily with industry participants and lobbyists for input on proposed regulations. No, what really matters at the end of the day is that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission is overseen by the House and Senate Agriculture Committees.

…

But investment bankers adapt. Change is the water we swim in, the air we breathe. We will adapt to whatever stupid new regulations and incompetent, undertrained, overmatched new regulators you throw at us. And we will come out on top, as always.It’s just too bad we’re gonna have to charge you extra for the added headache.

Classic. The important points though, are entirely valid – even that

last one that comes across as a smirk. Every regulation costs money to

comply with and that has to come from somewhere. I can guarantee you

that they are not going to be paying the people less as they need more

to comply with the regulations – and more smart people to work out the

best way to do so. The shareholders need to be compensated more for the

increased risk of investing. The buildings will not cost less.

The people who pay for all this are the depositors and borrowers – i.e. you. Oh – and the taxpayers. Oops – you again.

I will be adding this one to the blogroll.

[UPDATE]

If you want to have a look at a near final draft of the proposed changes, it is here. I understand this is the one most people are working off.

Another opinion is here. As this one is a Reuters blog, it is much cleaner. There are, for example, no uses of the “f” word.

Most popular