You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Banking Theory’ category.

I have not had much to say here over the last few weeks as work has been pretty intense. In the mean time, for those of you more interested in monetary questions, head on over to the Daily Kos for a good read on Hayek vs. Keynes.

Great quote from the piece – “Trying to cure a recession with more cheap credit is like trying to cure chemotherapy with more cancer.

I have been asked several times for a summary of what I think about the changes to the US banking system mooted by the Obama administration. Apart from not actually addressing the root cause of the collapse I believe the suggested changes will just make the whole thing more likely to recur next time the economy downturns.

The root cause, by the way, was over-lending by small commercial banks for mortgage purposes, aided and abetted by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, US regulations and bigger US banks that did not look too closely at some of their risk models in pursuit of short-term profits.

The best summary I have heard, though, and one that is close enough to my own views, is this one from the BBC, which I heard driving home yesterday. Give it a listen and then think about it.

Following a suggestion I have been reading a book by Naomi Lamoreaux on the development of banking in New England1. It is called Insider Lending: Banks, Personal Connections, and Economic Development in Industrial New England.

She makes a number of excellent points in the book, and, to me, anyone with an interest in the development of modern banking should give it a look. Quite a few of the points she makes relate to the way that the improving understanding of credit risk, and the development of modern risk management, was, to a large extent, responsible for the development of modern, large banks.

I would argue, consistent with my earlier post on regulation, that it was not solely this, as an increase in regulation did play a major part, but I think it was more of a virtuous (or perhaps vicious) circle – with an increase in the size of banks, and an increasing ability to lend to whoever happened to turn up to the bank driving further regulation – which then effectively forced the smaller banks to grow or perish – creating more regulation.

The central point of the book is simple – early banking in the US (and, she presumes, elsewhere) was severely hampered by an inability to assess credit risk, so what happened was when a bank was founded it generally had several directors, men (and they were all men) of substance who effectively both lent their names to the bank and risked a large part of their fortunes in the venture.

In return, what they got was access to the banks funds, with a typical bank lending between 20 and 50% of its funds either to the directors or family members of the directors – the “insiders” of the title. They were, to an extent, protected from unlimited liability by the bank’s charter, but this protection was often more illusory than real as to default would normally not only spell the end of the bank, but also the reputation of the individual directors.

The result was that the directors typically had an overwhelming say in the allocation of the bank’s lending, and they often lent to themselves or to others they knew well.

While today this may be looked on askance (and as possible criminal activity) then it was considered normal business for the reasons set out above. The difficulty of assessing credit risk meant that only lending to people you knew well (and, presumably trusted) was reasonably safe and, as you effectively had your own money on the line, you wanted to be really safe.

This had several effects – most people were effectively locked out of the banking system until they reached a point where they were rich enough to either own their own bank or to know someone who did. The second was that banks tended to be small – really small – with around 6 directors each and few employees. They also tended to have really high capital and liquidity ratios and charge really big margins. This then locked still more people out of the borrowing market.

The development of modern risk management practice, in all fields but particularly credit risk management, put paid to this model. While a few micro banks lingered into the modern era (and a few unit banks survive in the US) the bulk either went out of business or were bought out in the period up to the first world war.

The simple fact is that bigger banks, once you can overcome the difficulty of finding the good risks to lend to, are much, much more efficient2. If you can lend to more people, and people you do not personally know, you do not need your (comparatively expensive) directors to take every decision. You can directly obtain diversification benefits, cutting down losses per dollar lent. You can also, as a consequence, reduce your liquidity and capital ratios so you can drive more lending off the same amount of deposits (not, of course, that you can lend more than you have in deposits) and you can generally make more money.

For those campaigners for “social equity” it also makes a clear point – without modern risk management the poor are effectively locked out of the banking system entirely – so if they want (or need) to borrow funds they need to go to the loan sharks to get one. Personally, I would prefer to pay 6 to 10 percent to a bank than 20 to 50 percent to a loan shark. The bank also tend to not threaten to break my legs for non-payment. Banks can be funny that way.

The directors also become much more removed from the day-to-day operations,becoming more like the modern directors of a bank, able to reduce the risk to their own personal assets that may result from a bank collapse.

I would encourage readers to have a look for this book and give it a read, as it fills in a hole often left in the discussions on the development of modern banking.

.

1. For those not familiar with the term, or who may be thinking of another New England as there are several, she means the US states to the north east of New York.

2. They can also, as I pointed out earlier, deal with the regulation better, and they can lobby government more effectively – i.e. be more efficient rent seekers.

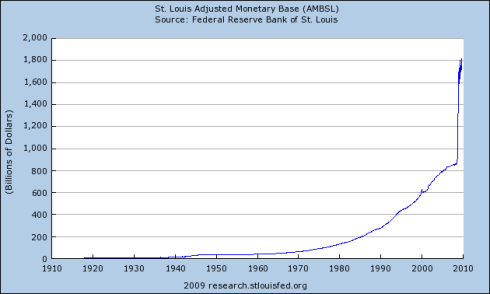

Following on from this post nearly a year ago I thought an update may be of interest.

Clearly, the situation has not improved greatly since then and the reservations I expressed about this last year are still relevant today – but if this story proves correct it may be that the situation is to be resolved at least in the short run. At least it has not got notably worse.The thing with the reverse repos, though, is that the money will eventually re-emerge into the systems as the deal(s) unwind, so this is only a temporary cut. Additionally, the paper that the fed would be issuing (if this is correct) will also normally be negotiable, so this is not as real a cut as it looks.

I am not sure if they intend to keep it that way (i.e. eventually allow all of that cash from the unwound repos to go back to the banks) or if they will be looking to unwind the position completely and return the monetary base to trend – i.e. about USD900bn, representing a long term withdrawal of about half of the current amount.

Either way, it looks like the gigantic experiment is set to continue for a little while yet – just with a little pause.

As for Australia – we could, by comparison at least, be said to be models of conservatism in monetary policy.

I will very irregularly have any time for a full post over the next few weeks due to work pressures. I seem to be spending most of my time here trying to sort out one commenter on what I believe to be his misunderstandings of banking. Oh well.

Just for your reading pleasure, though, I read a very good post regarding the role and future of the Credit Ratings Agencies on the usually excellent “The Sheet” today. Have a read – it is worth it.

Conclusion:

The agencies proved that they are poor at rating complex structured finance products. Their approach to rating sub-prime mortgage backed securities was not sufficiently rigorous and their models for assessing other more complex products were inadequate.

By virtue of this, their opinions on these products should now be viewed as being of little value and the market should effectively withdraw the agencies’ ‘licence’ to rate such products. This will open the door for new specialist structured finance ratings agencies to enter the market.

This seems a better approach than more regulation and the unintended consequences that could result.

If you are in the business of reading banking news on a regular basis please subscribe. It may help in your understanding of what banks actually do.

While this may be a little tangential to the normal run of posts here, to me managing regulatory risk is one of the things that any good risk manager has to do. Understanding the abilities and restrictions that the law has is an important part of that.

Over the last few months I have been putting the occasional post up here on what I feel is wrong with a lot of the regulatory framework. Skepticlawyer, being the very good lawyer she is, has done it better.

Legislation has two limits. One is practical (call it a ‘means-end’ limit). The other is principled (call it a ‘normative’ limit). Most philosophers spend all their time arguing over the latter: John Stuart Mill’s ‘harm principle‘ represents an attempt to get at what a principled limit on the powers of legislation may look like. This is philosophically interesting and forms a major part of my DPhil thesis here at Oxford. In the case of conservatives and social democrats, however, both groups engage in major legal wish-fulfillment: they think they can ignore ‘means-end’ limits. That is, they seem to think that passing a law will make it so. If wishes were horses, people, beggars would ride. They think they will, for example, be able to make abortion illegal (or greatly restrict access to it) with no social or economic comeback, or impose salary caps on business executives without hemorrhaging talent overseas or to other industries.

This is in the context of a piece on the Left in Australia – but the second half of the piece goes on to more general issues and it is this section of the post I would encourage you to read. It starts at the third paragraph after the blockquote in her piece.

I posted a comment on another blog a little while ago and, as it covers my (current) position on the question of whether bank deposits are money, I thought I would repost it here (after tidying up the spelling).

This one largely follows an old post here – but does expand in some ways on it.

I do not want to labour this point and I would be the first to say

that my opinion is not in full agreement with the mainstream of

economics. It does, however, come out of a long history of working in

bank treasury functions in several parts of the world.

The question of whether or not banks create money revolves around

whether or not a bank deposit counts as “money”, properly so called.

Personally, I doubt it is, as I cannot conduct payment transactions with

my bank account – I need to be able to withdraw the funds first. This

is a contractual question between me and the bank. Most of the time the

bank will honour the demand to pay the funds, so under most

circumstances the funds in my bank account are a close cash substitute

and can therefore be regarded as money, and I agree with Mark above on

that. In extremis, though, the bank may not deliver the funds –

so bank accounts are clearly less liquid than cash. That situation is

only likely to occur when the bank itself cannot deliver on the demand

for cash – i.e. there are more demands for withdrawals than the

individual bank has access to cash to meet those demands.

Really, then, the total pool of liquidity represented by any bank is not

the total amount on deposit with the bank, but the (much smaller)

amount they have in ready cash or other sources of funds to meet calls

for withdrawals.

You are right that a loan disbursement (or deposit withdrawal) from one

bank will often, even usually, result in a deposit with either that bank

or another – but this is generally not immediate, so the withdrawal or

disbursement is separated by time from any re-deposit, nor certain. It

may be that the funds withdrawn are not redeposited in any bank for some

time – they could be kept under the bed, used multiple times for

transactions or even go offshore.

The point here is that a particular bank cannot be sure where any

disbursed loan funds may end up and can only count on a small proportion

returning. This means that they cannot simply inflate their

balance sheet by making loans and counting on the funds to come back as

deposits. Additionally, if they did this their liquidity ratios (one of

the key measures of any bank’s soundness) would steadily deteriorate,

restricting their ability to make further loans. Their capital ratios

would also steadily deteriorate, reducing their ability to raise funds.

.

To me, then, the question of whether you measure the total money supply

to include or exclude deposits in the banking system is really

irrelevant. That may well be a standard (and useful) measure for

economic policy questions. However, to me, the total amount of funds actually available for transaction purposesin

an economy does not include bank deposits (whether chequing or

otherwise) but does include total liquid funds (cash, government bonds

etc.) held by the banks – a much smaller figure. It is not increased by

the actions of banks in depositing and lending – in fact it is reduced

by the amount of the solvency ratios.

I appreciate that this is not purely mainstream, but I know how these things operate in every bank I have ever worked in.

.

You may (OTOH) argue that, in the event of a likely bank failure to

deliver due to insolvency, the government is likely to step in – the

(either implicit or explicit) “printing press” contingency. That may

well be so – but if you are going to count the likelihood of the

government stepping in and printing as part of the money supply then

that should be explicitly acknowledged, not implicitly included by

counting all bank deposits. That then becomes further government created

money, not bank created money.

I have just started reading a book by Tim Carney entitled “The Big Ripoff” and he makes many of the points I have made time and again – the effects of regulation are generally not the ones you would expect.

The fans of regulation are generally taken to be opponents of “Big Business” and they call for more regulation as a counter to the (alleged) pernicious effects of having large companies. Most of these effects are easy to see – strong pricing power, reduced service and many other things that are bad for the consumer.

The argument that Carney puts forward, though, is one I have been making for some time – both on this blog and elsewhere. The argument is a simple one. The more regulation you have in a market the more that regulation will favour the big suppliers – i.e. the larger incumbents – over the smaller incumbents, any potential new players, and, crucially, the individual consumers. So the more that you regulate the worse the situation gets for everyone but “Big Businesses”.

The reasoning is simple to see if you think about it – compliance is expensive. I know this as a simple fact – and my fee base confirms it. It costs money to comply with regulation. The more complex it is the more expensive it gets. For example – complying with the (old) Basel I Accord was a simple exercise. While it took a fair amount of work to get compliance when it first came in in 1988 / 89 most banking systems could comply with it fairly quickly and, importantly, cheaply.

While Basel II is a much better (i.e. risk sensitive) set of standards there is (I think) no-one out there that would claim they are simpler than Basel I. The amount of money that even a small bank following the Standardised / Basic methods of compliance had to spend was a fair leap from the amount they had to spend to spend under Basel I, and the amounts you have to spend to comply with the Advanced methodology (and therefore to get a substantial capital advantage) was many, many times more.

There is simply no way that a small bank or a new player can afford this without the belief that they will become a big bank (and therefore Big Business) as a result.

Even to keep the people needed to continue and upgrade these systems is expensive and needs a high (and profitable) turnover. There is no other way.

All of this means one thing – that more regulation makes it relatively more expensive for small businesses to operate that for large businesses and it imposes high barriers for new entrants into a market. Regulation therefore tends to help big business, not hinder it.

BTW – I should add that a post at catallaxy reminded me to write this one.

It’s good to know that I am not the only one looking at this proposal and not knowing whether to laugh or cry. The post titled “A Mighty Wind” over at The Dealmaker’s blog is well worth a read. Just watch it though – the language is not entirely worksafe.

There are some great quotes in there:

Forget the no doubt significant fact that substantial portions of the Administration’s regulatory proposals were authored by products of a government-to-industry-to-government merry go round like Hank Paulson, Larry Summers, and Tim Geithner. Forget the fact that the Administration is said to have consulted heavily with industry participants and lobbyists for input on proposed regulations. No, what really matters at the end of the day is that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission is overseen by the House and Senate Agriculture Committees.

…

But investment bankers adapt. Change is the water we swim in, the air we breathe. We will adapt to whatever stupid new regulations and incompetent, undertrained, overmatched new regulators you throw at us. And we will come out on top, as always.It’s just too bad we’re gonna have to charge you extra for the added headache.

Classic. The important points though, are entirely valid – even that

last one that comes across as a smirk. Every regulation costs money to

comply with and that has to come from somewhere. I can guarantee you

that they are not going to be paying the people less as they need more

to comply with the regulations – and more smart people to work out the

best way to do so. The shareholders need to be compensated more for the

increased risk of investing. The buildings will not cost less.

The people who pay for all this are the depositors and borrowers – i.e. you. Oh – and the taxpayers. Oops – you again.

I will be adding this one to the blogroll.

[UPDATE]

If you want to have a look at a near final draft of the proposed changes, it is here. I understand this is the one most people are working off.

Another opinion is here. As this one is a Reuters blog, it is much cleaner. There are, for example, no uses of the “f” word.

This so-called “new” regulatory “system” for the US – at least on the first draft – looks like it is simply going to add a few more regulators into an already over-governed financial system. Adding in more regulators to a system in which, even at the lowest count, there are more than 54 I cannot see as an improvement. From prior experience all I can see it doing is increasing the amount of buck-passing, adding yet another reporting layer and making it even less clear than it already is as to who it is a given financial institution has to listen to.

If you are going to have a regulated system at least make it bloody clear who is responsible and then give them the powers to deal with most, if not all, problems. Then trust them to do their jobs – i.e. get out of the way.

The Australian example is a good one – the government delegated regulatory powers to APRA. There is little doubt over who regulates what – in Australia APRA deals with systemic and individual financial institutional risk – banks, insurers, the lot. The ASX deals with listed companies where it has anything to do with information to shareholders. ASIC deals with companies and any non-APRA regulated small financial entities. The individual States have some responsibilities with respect to consumer protection. AUSTRAC deals with money laundering and some elements of criminal behaviour. The Federal Police deal with other alleged criminal activity.

Even that takes a while to say – and does leave some overlaps, but it is nothing compared to the situation in the USA. At least I can get most ofthe Australian system into one paragraph.

I have always thought the correct way to deal with a mess was to tidy it up. The suggested system seems to amount to clean up a mess by throwing more rubbish on it. It is an innovative solution to the problems – but I cannot see it as brave, useful or intelligent. The US has only just sorted out how to go to Basel II – it has not yet been implemented.

If I can put in my suggestion – other than a free banking system (unlikely to be politically possible) the best solution would be fairly simple. Make the Fed responsible as the sole regulator of all non-State chartered financial institutions, insurance and banking alike. Close the FDIC and allow private sector insurers into the market. Close the OCC and all of the other parts of the alphabet soup that are currently failing to do their jobs.

Close down Fannie, Freddie, Sallie, Maggie (or whatever the rest are called) and the rest – if they need a federal guarantee (implicit or explicit) to do their jobs then they probably should not be doing it. Sell off all of their assets and then the US government makes good on all outstanding liabilities – and the shareholders lose their holdings unless by some miracle they are actually worth something.

Replace US accounting standards with proper ones – IFRS will do. The Fed then implements Basel II the way they wanted to do it (which is also the should be done) – not the half-arsed way they have had to do to get it past the FDIC.

Get all that done and you would have a “New Regulatory System” – and one you could be proud of. As it is you are just going to make a bad situation worse.

Most popular